" The Berkeley fire began in Wildcat Canyon around noon, and by 2:20 p.m. — spread by fierce “Santa Ana” winds — had rolled into the city limits. At 2:30 p.m., aid was requested from Oakland, Alameda, Emeryville, Piedmont, Richmond and Hayward. The Oakland Fire Department had 13 fires burning at the time of the call and was not immediately able to provide assistance" (from the Berkeley Conflagration of 1923).

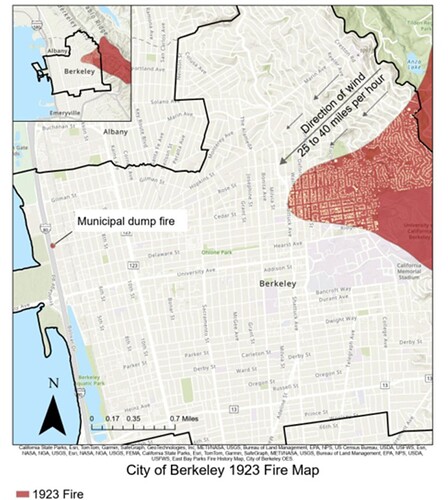

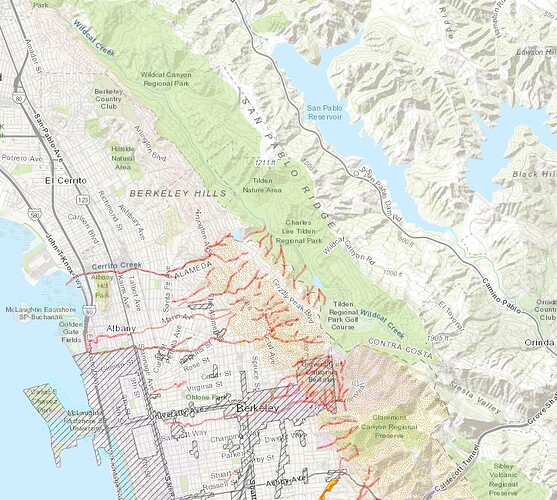

A modern reconstruction of the 1923 Fire shows this imprint:

This reconstitution appears fairly accurate as the following analysis shows.

According to the Report on the Berkeley, California Conflagration of September 17, 1923, issued by the National Board of Fire Underwriters’ Committee on Fire Prevention and Engineering Standards (hard to find but available at Stanford U stacks) The fire began around 12:10 or 12:15 p.m., in an area of a trail alongside a power line on the east slope of the San Pablo Ridge. While the origin was at first attributed to the power line, later a careless smoker was suspected. The fire remained east of the Berkeley ridge for close to two hours. Eventually, though, helped by Diablo winds blowing 25 to 40 mph, it jumped the ridge:

“When it did, near Berryman Reservoir, the fire was a half mile wide. A thick black cloud came pouring over the hill, followed by surging flames pressed low by warm, gale-force winds, known as Diablo winds. The fire raced down Codornices Creek and bore down on the Northside neighborhood that ran from the creek to the northern edge of the Berkeley campus at Hearst Avenue.” (from When Berkeley Burned - Cal Alumni Association, Spring 2019)

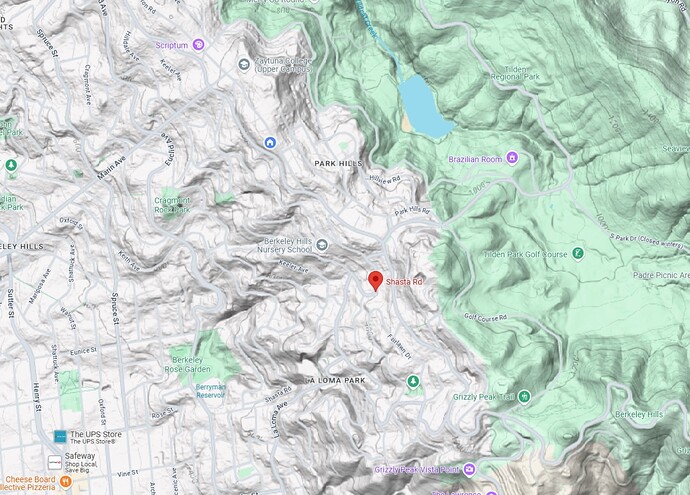

The relief map explains clearly what must have happened.

With strong NE winds behind it, the fire passed immediately south of Lake Anza, then climbed the E side of the Berkeley Ridge along Park Hills Rd and Shasta Rd, and arrived right around where Shasta Rd meets with Grizzly Peak. It can’t have been much further North, or it would have raced down the N side of Codornices (we know it didn’t because, according to the Tribune, “[it left] untouched beside it the Codornices Club” which was in the NE quadrant of Codornices Park). It can’t have been much further South, or it would have missed Codornices Creek altogether. Instead, it raced down the South side of Codornices Creek, and lit up its first structure at 125 Shasta Rd (marked in red in the relief map), the house of Arthur Brodeur, professeur of Scandinavian Studies at UC Berkeley, before racing downhill. Eventually, it would destroy 584 buildings and one whole square mile of the city.

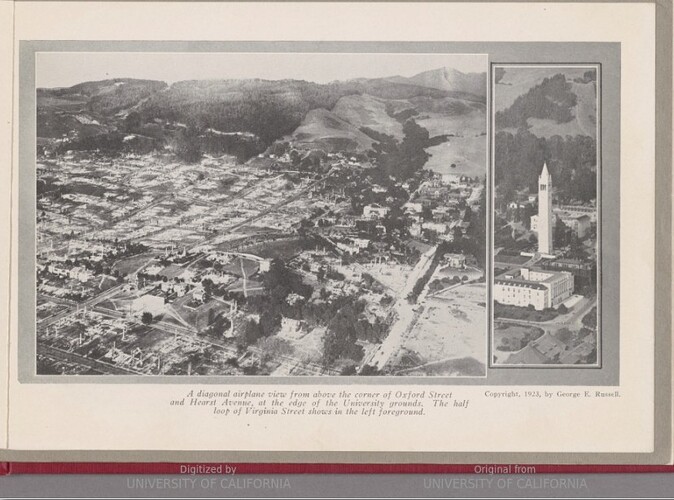

source: Aubrey Boyd via HathiTrust

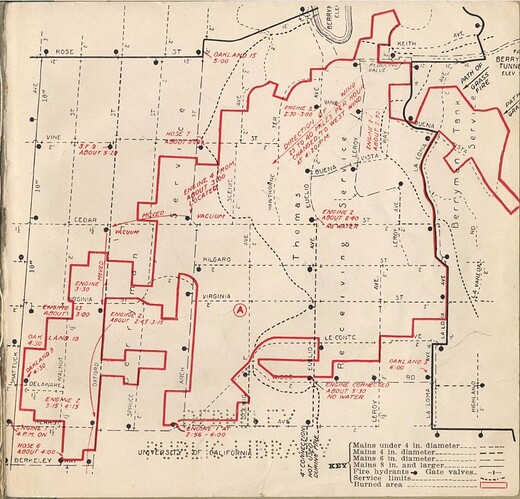

Berkeley Fire Department’s records show this map of the fire outline:

source: Story of the Berkeley Fire via Berkeley Public Library [PDF]

It is interesting to note that one can today still find some remnants of the boundaries of the fire by looking at the roofs. The original houses were wood shingles, a la Maybeck. But, "“in the aftermath, replacement homes were built with fire-resistant stucco siding and clay tile roofs, creating a delineation in house design that marks the path of the fire to this day.”

(from September 17, 1923: The Day That Berkeley Burned - Cal Alumni Association).

For those of us living on or near the Berkeley Ridge, though, it is particularly important to understand the early genesis of the fire. What happened before it jumped the ridge? The modern reconstitution shows an ignition point on the E side of Wildcat Canyon, as the origin of the fire is often reported. It is very hard to understand, then, why the fire, subjected to NE Diablo winds, did not climb the W side of Wildcat Canyon and jump the Berkeley Ridge much further North than Lake Anza.

However, the [Report on the Berkeley Conflagration issued by the National Board of Fire Underwriters’ Committee on Fire Prevention and Engineering Standards, a group of multidisciplinary experts, states that the fire started around 12:10 or 12:15 p.m., in an area of a trail alongside a power line on the east slope of the San Pablo Ridge. San Pablo Ridge is the ridge immediately east of Wildcat Canyon:

source: Berkeley GIS Portal

So the fire must have ignited further East from where it is normally reported (or shown on the modern reconstitution). How far North did it start?

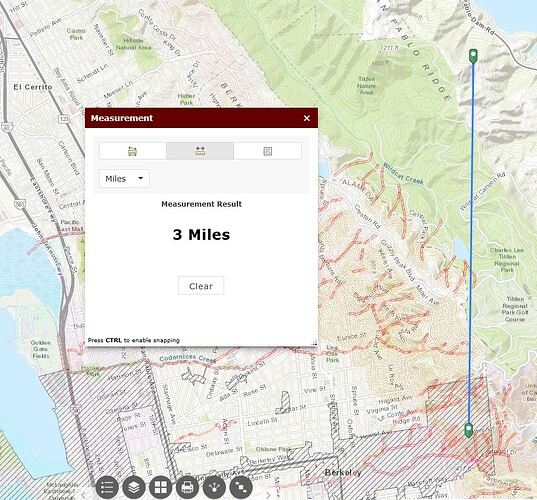

At the time, Woodbridge Metcalf, professor of forestry at UC Berkeley, wrote in “Hill Fire Protection, Near Berkeley, California,” that ignition started 3 miles north of the city. Measuring 3 miles N roughly from the Campanile, this is what we get:

source: Berkeley GIA Portal

This makes much more sense: now, we can understand how the fire would remain, for a while, E of San Pablo Ridge, long enough to pass E and S of Lake Anza before being routed over the Berkeley Ridge.

At 2:05pm, Berkeley Fire Department gets report of a fire in town. If ignition really occurred around 12:10pm, then the fire must have progressed a bit faster than a mile an hour, a very reasonable rate with such strong winds, and fairly compatible with the progression of the fire in the later part of the afternoon:

Source: Berkeley GIS Portal

What does it mean for the inhabitants of the Berkeley Ridge?

There is not much land east of the San Pablo Ridge, because of the presence of the San Pablo Reservoir. A Diablo wind fire starting east of the San Pablo Reservoir would probably end up routing south of it, since Diablo winds blow from the north to north-east, and possibly become a severe danger to LBL and campus. On the other hand, a fire starting sufficiently north of the San Pablo Reservoir would likely jump the San Pablo Ridge north of San Pablo Reservoir, then would almost inevitably run down Wildcat Canyon and erupt on the North Berkeley Ridge somewhere between Kensington and Zaytuna college. Once over the ridge, it could run west and south over the whole of North Berkeley, including, of course, the previously burned area up to Hearst and Shattuck, but also much further north.

More good reasons to create plenty of defensive space around our homes!

References

- 1923 Berkeley fire: A look back at the blaze 100 years later

- 1923 Berkeley fire: How a disaster changed the fabric of the city

- Could a fire like 1923 hit Berkeley again? Experts say "no doubt"

- The Story of the Berkeley Fire [PDF]

- September 17, 1923: The Day That Berkeley Burned - Cal Alumni Association

- 1923 Berkeley fire - Wikipedia

- Berkeley Historical Society and Museum - The 1923 Fire: Berkeley’s First Wildfire Disaster