The Great Fire of 1923 destroyed almost 600 structures in Berkeley, and one square mile of town. In fact, it was the worse fire in California history for 67 years, until the 1991 Tunnel Fire.

In reading the reports about the 1923 fire, one would have thought that a wall of flames came down from the Berkeley Ridge, consuming all the houses it met on its path:

"By two in the afternoon of September 17, 1923, just about everyone in Berkeley had taken note of the uncommonly warm, dry wind blowing in from the northeast. What they didn’t know was that a small grass fire over the hill in Wildcat Canyon was growing fast, leaping from grass to brush to tree—and it was about to crest the hills of North Berkeley.

When it did [crest the hills], near Berryman Reservoir, the fire was a half mile wide. A thick black cloud came pouring over the hill, followed by surging flames pressed low by warm, gale-force winds, known as Diablo winds. The fire raced down Codornices Creek and bore down on the Northside neighborhood that ran from the creek to the northern edge of the Berkeley campus at Hearst Avenue." (from September 17, 1923: The Day That Berkeley Burned - Cal Alumni Association, written in Spring 2019).

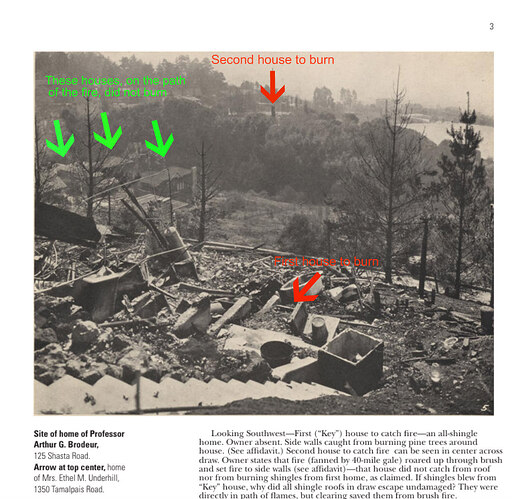

The reality is different, and shows evidence of an ember fire. Below is a picture of the first two houses destroyed by the fire:

source: Berkeley library [PDF]

The view is taken facing the southwest. The Berkeley Fire Department clearly identifies, at the time, that the wind in that area was blowing from the N/NE, and the grass fire down Codornices Canyon was moving to the SW.

The “Key” house, first to burn, is in the foreground, at 125 Shasta Rd (Shasta numbers have changed since: this would have been near Shasta & Queens). Several houses on the path of the fire, pointed at in green, survive unscathed. The next house to burn is a quarter mile downhill, at 1350 Tamalpais. It is clear that the fire must have been ignited by embers blowing down and finding opportunistic fuel.

Quantities of other evidence point in the same direction. For instance, the Report on the Berkeley, California Conflagration of September 17, 1923, issued by the National Board of Fire Underwriters’ Committee on Fire Prevention and Engineering Standards, mentions:

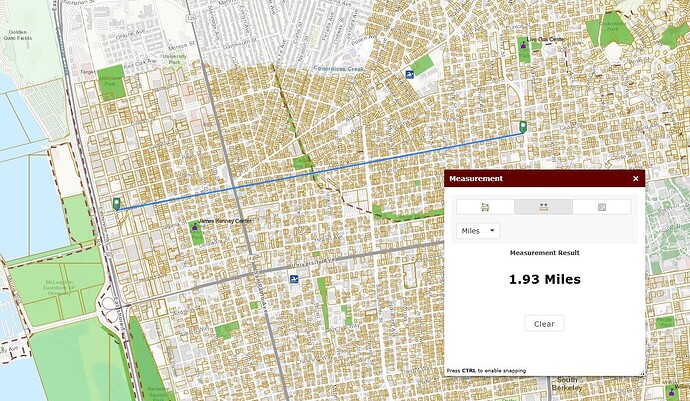

" Engine Company 5 […] helped control a fire at the municipal dumps at the foot of Cedar street." The municipal dump was near Cedar and 2nd St. The raging fire never went beyond Shattuck Ave., but embers from the fire were driven by the wind to the dumps almost two miles away!

Another example, coming from the same report: “Chemical Company 4, after extinguishing several roof fires, was stationed at the Regent street fire station.” So Company 4 was going around town extinguishing roof fires (most of them, no doubt, from wood-shingled roofs), obviously also caused by embers flying over town.

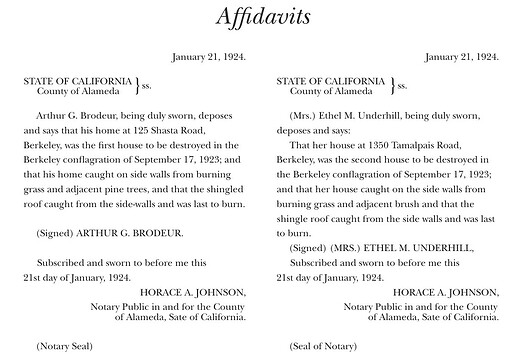

It is interesting to read, as a side note, that both houses #1 and #2 were ignited by grass and shrubs burning in the proximity of the house, and not by a roof fire:

It is quite possible that both houses (and possibly many more) could have been saved by Zone 0 and Zone 1 defensive space practices.